Three CNN reporters on three continents wore chemical-tracking wristbands. The results were alarming

The wristbands arrive from a lab in the Czech Republic encased in a small silver tin. They land on the doorsteps of three CNN reporters: one in New York City, one in London and one in Hong Kong.

Unboxed, these black silicone bands look unassuming, but their simplicity is deceptive. They can mimic human skin and absorb chemicals we are exposed to daily, many of which come from plastic products.

Plastic is woven into our lives. It’s everywhere, even places we might not consider, such as clothes, furniture and the linings of cereal boxes. The chemicals it contains slowly leach into the air we breathe, the dust we inhale, the food we eat.

Most plastic products come with no information about the chemicals they contain, leaving people clueless about what they are being exposed to.

It’s an invisible problem with potentially catastrophic health consequences, said Leonardo Trasande, a professor of pediatrics and population health at New York University’s Grossman School of Medicine, who studies the impact of chemicals on humans.

“The chemicals used in plastic are now extremely well known to contribute to disease and disability that cuts across the lifespan, from cradle to grave, from womb to tomb,” he told CNN.

The chemical-tracking wristbands turn the invisible into visible, said Bjorn Beeler, the executive director of the International Pollutants Elimination Network, or IPEN, which provided the wristbands. The organization uses them for research experiments only, they are not commercially available.

Each band can pick up 73 chemicals associated with plastics, spanning six chemical groups, although they do not pick up PFAS, so called forever chemicals, which linger for years in the body.

The wristbands are “non-invasive, you don’t have to test blood or urine,” Beeler told CNN. While they cannot measure the concentrations of chemicals inside our bodies, studies have shown the exposures they detect correlate with presence of the same chemicals in peoples’ bodies.

We wear them for five days as we walk around busy polluted cities, commute to work in tech-filled offices, take children to school, cook, clean, and apply lotions and perfumes.

At the end of the experiment, we carefully place the wristbands back into the silver boxes and send them to the lab for analysis. The results arrive several weeks later. The tale they tell about the toxic landscape each of us wades through every day is chilling.

A cocktail of chemicals

Plastic was a miracle that revolutionized life, granting the ability to make products we never could before. They transport clean water to those that desperately need it; they prolong the shelf life of fresh food; they make modern, life-saving medicine possible — the list goes on and on.

But as plastic has proliferated, especially in its single-use versions, it has created a crisis. Plastic waste is everywhere from the highest mountain on Earth to the deepest part of the ocean. It’s an environmental catastrophe and a climate disaster — most plastic is made from planet-heating fossil fuels.

A much less understood aspect of the crisis, however, is the health impact of the complex cocktail of chemicals plastic contains.

There are more than 16,000 plastic chemicals, according to a study published last year in Nature (although the International Council of Chemical Associations, an industry body, has verified far fewer in products in its publicly available database of plastic additives).

They are added to make plastics stronger, more flexible, longer-lasting, colorful or fire-resistant. “They help optimize materials for specific uses and reduce waste by extending product life and functionality,” said Kimberly Wise White, vice president of regulatory and scientific affairs at the American Chemistry Council, an industry association.

But at least 4,200 pose hazards to human health and the environment, the study found. Around 10,000 others have not yet been tested for potential hazardous impacts.

“The chemical complexity is just striking,” said Martin Wagner, a biologist at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology and an author of the Nature study.

Examples of products that can contain harmful chemicals:

Sources: National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, US Food and Drug Administration, Washington State Department of Health Graphic: Leah Abucayan, CNN

Chemicals are released at all stages in the lifecycle of plastics and can infiltrate our bodies.

Even very low levels of exposure can be harmful, experts say. Many of these chemicals are “endocrine disruptors,” meaning they can “hack” hormones that control everything from growth and reproduction to metabolism, by altering the way they work, Trasande said.

The proliferation of thousands of different chemicals, with new ones produced all the time, also exposes people to a cocktail of substances, which could make their collective impact greater. “Instead of one plus one equals two, it’s one plus one equals three,” Trasande said.

Plastic workers, who can be exposed during production, recycling and disposal, are among those most at risk, but few can escape. “It’s everyone’s problem, and we don’t know what we are dealing with,” said Tridibesh Dey, an anthropologist who studies plastics.

‘Everywhere, everyone chemicals’

We were uncomfortably aware of what we might be being exposed to on the days we wore the wristbands. What was in the fragrance we spritzed on before work? What might we be breathing in on busy roads or in our homes? What was the impact of the vast array of electronics in our newsrooms?

When the results arrived weeks later, they revealed each of us had been exposed to a toxic stew — an average of 28 different chemicals over the 5-day period.

There were individual differences between the three wristbands — we all have our own exposure depending on lifestyle and geography, said Sara Brosché, a science adviser at IPEN — but the similarities were much more striking.

Far and away the highest exposure levels for all three of us related to one group of chemicals: phthalates.

These additives make plastic more flexible, soft or stretchy and are in a huge array of products including food containers, kids’ toys, clothing and furniture. They’re also used in perfumes, lotions and other personal care products to carry fragrances and improve textures.

These are “everywhere, everyone” chemicals, IPEN’s Beeler said. “Every time we’ve tested anybody, they have it.”

All three of us were also exposed to a family of chemicals called bisphenols, present in electronics, car parts, toys, household appliances, receipts, water pipes and the linings of metal food and drinks cans.

Perhaps the most well-known is BPA, which was used in baby bottles and sippy cups in the United States until parents started to shun it over health fears.

Phthalates and bisphenols, both of which can wreak damage on the hormone system, have a slew of negative health impacts, according to a large and growing body of science.

Phthalates have been linked to fertility problems, premature birth, behavioral disorders in children, obesity, depression, cancer and cardiovascular disease.

DEHP, a common phthalate, and the chemical to which all three of us had the highest exposure, was responsible for around 13% of all cardiovascular deaths among people aged 55 to 64 globally in 2018, according to a recent paper co-authored by Trasande.

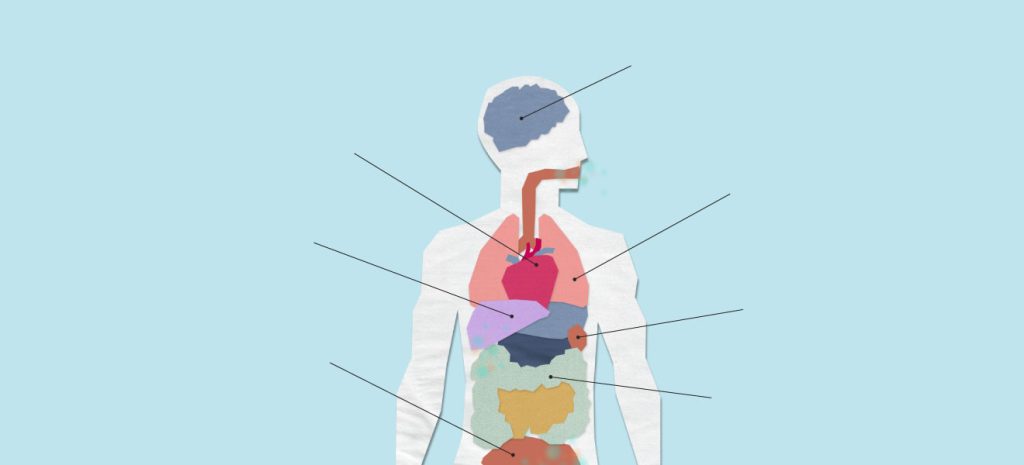

Exposure to certain chemicals in plastics is linked to higher risks of developing a wide range of health conditions:

Note: The sources all analyze health risks linked to phthalates and/or bisphenols.

Sources: National Institutes for Health National Library of Medicine, Environment International, Environmental Research, University of Manchester, Columbia University, Environmental Sciences Europe, The Lancet Graphic: Leah Abucayan, CNN

Bisphenols, meanwhile, have been connected to fetal abnormalities, low birth weight, neurodevelopmental disorders in children, earlier puberty in boys and delayed puberty in girls, increased risk of diabetes, heart disease and cancer.

A study published last year looking at 38 countries linked more than 160,000 deaths and more than 5 million cases of heart disease to just three chemicals: BPA, DEHP and a flame retardant.

While a large body of evidence is building on these more well-known chemicals, there are thousands more about which we still know little to nothing, Wagner stressed: “We’re dealing with quite a big mess.”

Perhaps most concerning are the potential impacts of these chemicals on children, who are now exposed while still in their mothers’ wombs, Wagner said. Children “take up many more chemicals, have fewer defenses,” and the health effects will play out over decades, he added.

A growing problem with few safeguards

Plastic production shows no sign of slowing. Now, as the world shifts to renewable energy, plastics represent a new frontier for the oil and gas sector.

Production is predicted to soar 70% by 2040 if current policies don’t change, and that means more chemical exposure.

Many countries regulate chemicals in plastics, but rules are often patchy and limited to certain products.

Several phthalates aren’t allowed to be used in children’s toys as well as a range of other products in the US, United Kingdom and Hong Kong.

BPA has been banned from baby bottles in Europe since 2011 and from food contact products since January. The US Food and Drug Administration stopped authorizing the use of BPA in baby bottles, sippy cups and infant formula packaging more than a decade ago. But the FDA hasn’t banned BPA in other food contact products, saying it considers approved levels to be safe.

Even where bans are in place, the chemicals produced as replacements can be just as harmful, if not more so, Trasande said. He calls it “chemical whack-a-mole” — as soon as scientists have shown a chemical is linked to problematic health impacts, it’s replaced with a new, untested one and scientists have to start all over again.

The answers to the problem are clear, Wagner said: Companies need to invest in making better chemicals and producers need to tell people what chemicals go into their products.

“Nonetheless, industry has refused to make any kind of progress … even worse, they have slowed down regulation,” Wagner said. He blames powerful lobby groups and vested interests for blocking action.

Some experts hoped a potential global plastics treaty, the subject of years-long negotiations, could boost efforts to regulate harmful chemicals, but the latest round of talks collapsed in failure in August.

Wise White of the American Chemistry Council said the industry is “committed to sound chemicals management and improving transparency.”

She said the International Council of Chemical Associations database has “easily accessible toxicological data” available for 90% of the chemicals it lists. “This challenges the narrative that chemicals in plastics are unregulated or unknown and underscores that robust data already exist to guide decisions and protect public health,” she added.

What you can do

The health impacts of plastics may be alarming, but there are fairly simple ways people can reduce their exposure to many of them, experts say.

Trasande advises using glassware and steel products instead of plastics for food and drinks. People should also avoid microwaving plastics and putting them in the dishwasher as these are “straightforward ways” to get chemicals into your body, he said.

Other advice includes giving children toys made from wood or silicone, avoiding processed foods which are likely to have had more contact with plastic, checking makeup and skincare ingredients for phthalates and ensuring good air circulation in homes and workplaces to avoid the buildup of chemical-laden dust.

Phthalates and bisphenols have relatively short lives, meaning they don’t stay in your body long. That means these measures can have a speedy effect. “We’re talking about days here,” Trasande said. If people can sustain these measures long term, they can reduce their chronic disease risk, he added.

Ultimately, however, it’s hard to fully control your environment. “If you wanted to live in a bubble up in the woods, maybe you could, but that’s not life,” IPEN’s Beeler said.

This seems to be the ultimate takeaway from the wristband experiment: All of us are being exposed to unknown amounts of chemicals every day, many of which may pose health hazards, with no real ability to know exactly which ones are in our bodies and in what concentrations.

The situation is likely far worse in developing countries, where there are fewer restrictions on harmful chemicals and higher exposure levels.

“You have no idea what’s around you and you’ve not really given consent,” Beeler said. “We are the canary. Everyone’s a canary.”

Laura Paddison, Jessie Yeung, Nill Weir.

Source: CNN Climate

October 2025